In the introduction, I shared my hope to really explore the heart of Batman, not just as a character in DC comics, but especially as a one that continues to captivate our world. I can't imagine a better story to kick things off than “Shaman,” scripted by Dennis O’Neil, drawn by Edward Hannigan, and colored by Richmond Lewis, the unsung hero of this arc’s visual glory.

Quickly summarized, “Shaman” (told across Legends of the Dark Knight #1-5) is one of Batman’s earliest missions. He’s up against a mysterious death cult whose use of obscure Native American myths from his past causes him to contemplate his future as a crimefighter. The story borrows its narrative foundation from Frank Miller’s & David Mazzuchelli’s seminal Batman: Year One (1987) as well as some elements from Tim Burton’s Batman film (1989), which premiered just a few months prior to the release of this book.

I’ll mainly focus on the power of the story and its enduring artistic accomplishments. But since I am reading these comics in their original format, I just can’t help but comment on some of their charming quirks: advertisements, editorials, and fan responses. I may mention these things in a “Post Script,” similar to the A.V. Club’s “Stray Observations.”

Finally, I don’t imagine I’ll preface every post with an explanation of what I’m trying to do, but while I’m still figuring out a common format for future posts, I’ll probably continue to give a brief preface (and hopefully, a brief post, too). So, here… we… go!

Shaman: Book One

Bruce Wayne is a man of science and courage. But more importantly, Batman is.

When Bruce returns home from his 12 years of training, he unpacks the curiosities that he’s collected in his travels. One of them is A Treatise on the Criminal Mind by Sir Maxwell Floppy, a fictional Victorian criminologist. Bruce cracks open the book while sitting on the floor of his palatial library. He smirks and calls out to his ever-indulgent butler Alfred, “Listen to this… ‘Criminals are a superstitious and cowardly lot.’” The idea of the Batman begins to grow in his mind.

Devoted fans will recognize the words. Originally, they were part of a contemplative soliloquy in Detective Comics #33, published 50 years before (to the month!) this inaugural issue of Legends of the Dark Knight. Over the course of time, the phrase became an oft-repeated ethical refrain; a guiding thesis for Batman’s vigilant interventions. And I think—in this world—there’s something vaguely true about it: these criminals are both superstitious and cowardly. The microcosm of Gotham City has always been oddly pre-modern: vulnerable to vengeful apparitions, ancient curses, mystical talismans, and the like. In their innermost parts, even lowly henchmen understand that Gotham is ruled by principalities and powers—some flesh and blood; some other-worldly—but all insidious. So they kowtow to whoever scares them the most: the Joker, Carmine Falcone, or R’as al-Ghul. These criminals are not only superstitious, but cowardly. Their deference to crime lords and terrorists is self-serving. Their reward is the pleasure of subduing their neighbors; thieving away what doesn't belongs to them. They cynically feign superiority. They say they understand the way the world really is—readily vulnerable and easily exploited. They’re just doing what’s inevitable in the the organized chaos of Gotham. But that proves to be a cheap idolatry—a valuing of trinkets and titles above charity and community. So they’re cowards in this sense, too.

But not Batman. He’s a man of science, not superstition; a man of courage, not cowardice. Ironically though, I think Bruce overlaps with the criminals he reviles more than he’d ever admit. No, he doesn’t use his skill and craft for evil, but his tendency towards philosophical materialism actually undermines his life’s endeavor to protect the weak and punish the oppressor. If this world of skin and bone is all there is, why wage a war to stop it?

But that’s what’s so great about the “Shaman” storyline. It exposes the world as deeply enchanted; imminently mysterious. Even our capable hero has plenty to learn about human nature and the spiritual world.

Our story begins two years prior to the advent of Batman. Bruce is in Northern Alaska, learning how to be a tracker and bounty hunter from Willy Doggett, the best at both. They trek through completely inhospitable territory, searching for Thomas Woodley, a notoriously vicious killer. Woodley catches Bruce and Doggett off guard, kills Doggett, but then falls to his own death after a slug-fest with Bruce. In the skirmish, Bruce loses his coat and pack and is forced to find civilization without his gear in sub-zero temperatures.

“I should pray for a miracle. I haven’t believed in miracles since my parents died.”

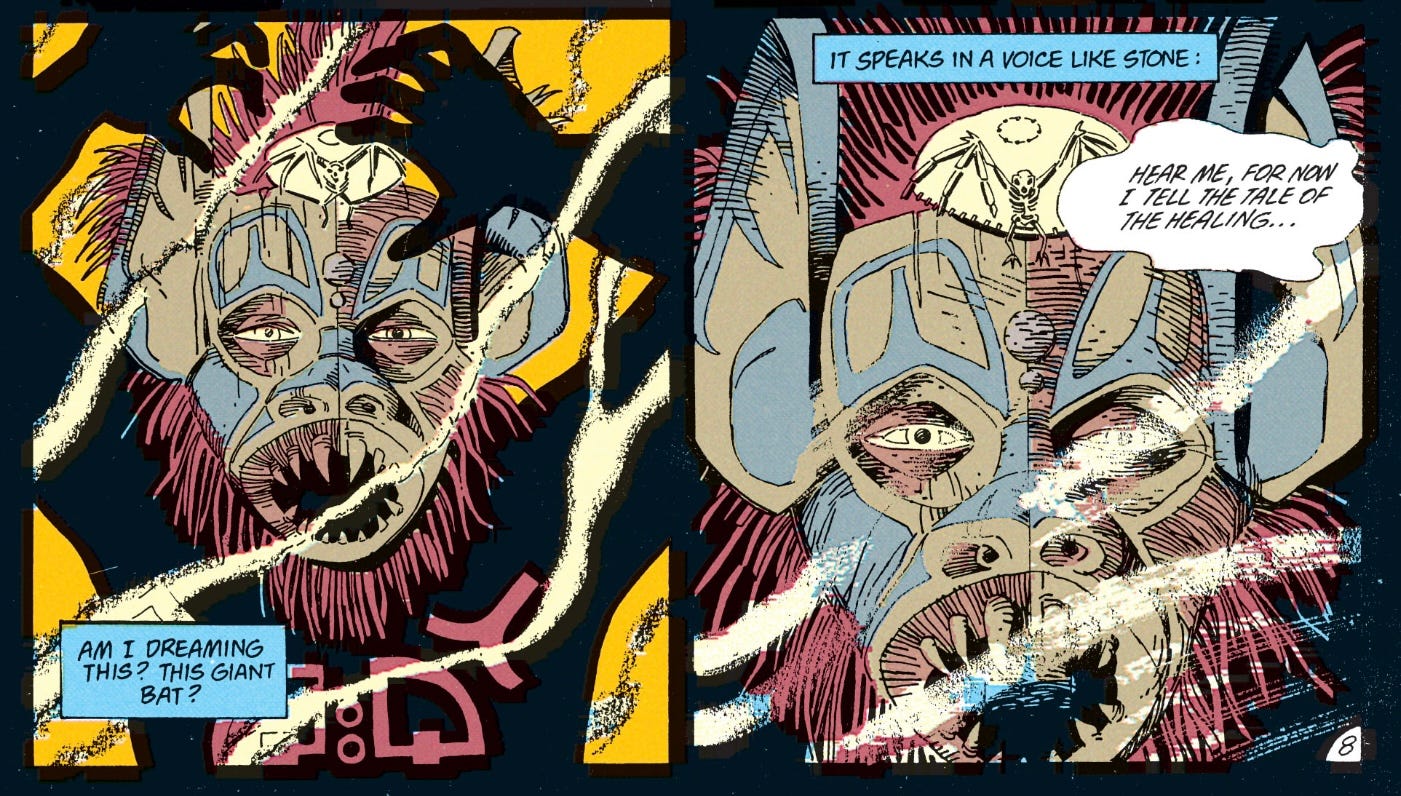

This is the voice we often hear from Bruce: angry, skeptical, and disenchanted. Finally he collapses, and slips into a horrifying dream, reliving his parents’ murder again with phantasmic sights and sounds. He comes back to reality long enough to see strange faces staring down at him, and one in particular—a giant, anthropomorphic bat—that tells him a story: “the tale of healing…”

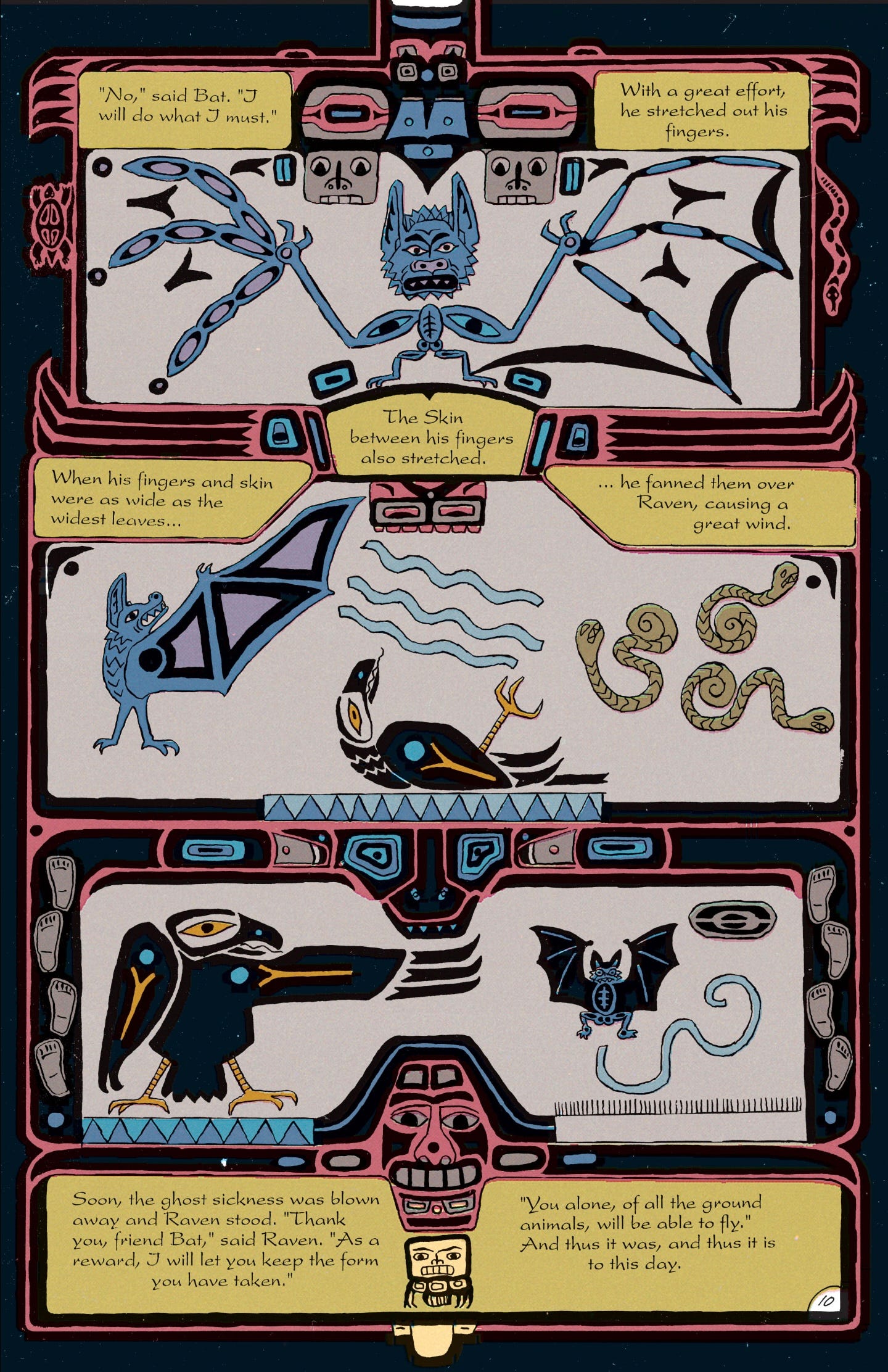

The story has the cadence of a Native American creation myth with biblical themes of Sin and the Spirit; of redemption and transfiguration. A “ghost sickness” personified as malicious serpents overcomes Raven, the friend of Bat, who is a wingless rodent. But out of great love for his friend, Bat stretches out his fingers and arms until they take the form of wings. He then beats his wings towards his friend and blows the sickness away. As a reward for his faithfulness, Raven allows Bat to keep his wings:

“‘You alone, of all the ground animals, will be able to fly.’ And thus it was, and thus it is to this day.”

Remind you of anything? It’s an interesting reversal of the Genesis 3 imagery of the Serpent being cursed by having his limbs taken away, forcing him to crawl in the dirt for all his days. Here, instead, the Bat is blessed by having his limbs transformed into wings and given the gift of flight. It also interesting that serpents, like the singular, biblical one, represent a “ghost sickness,” some notion of death and dismemberment.

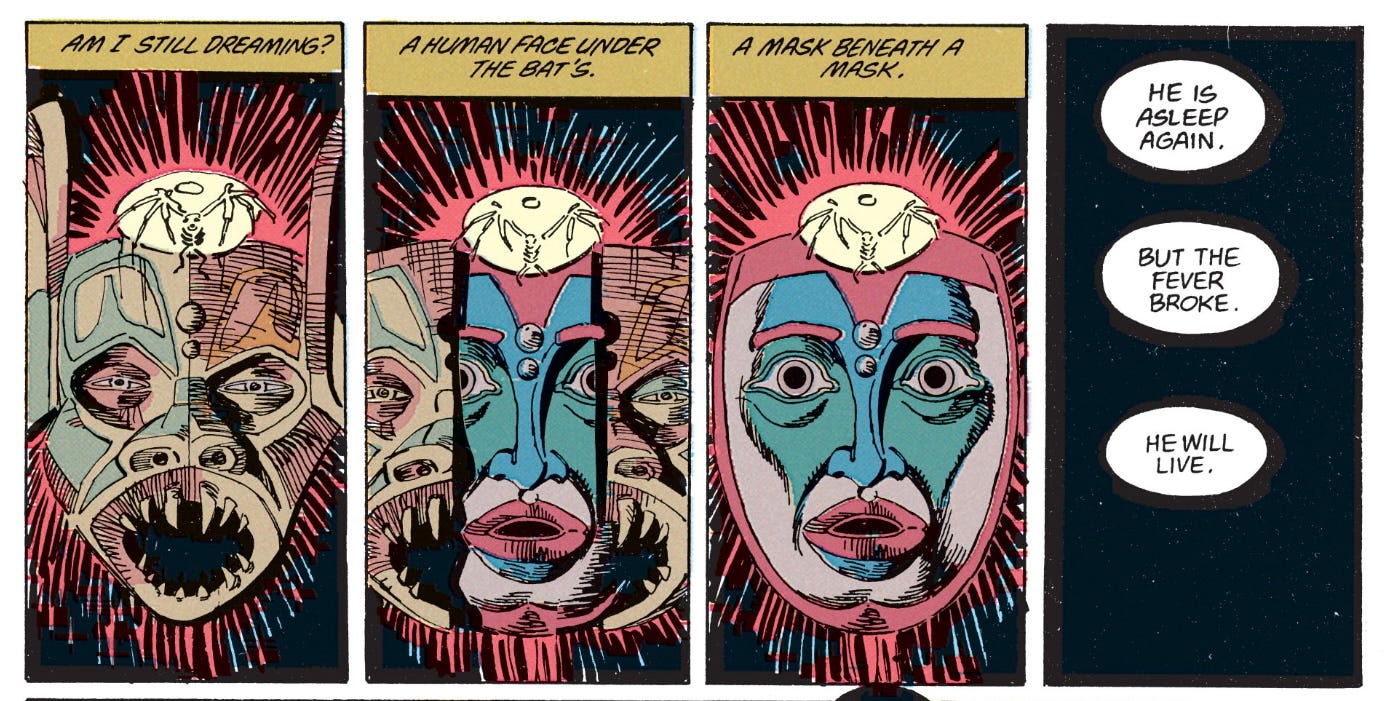

Bruce sees the ancient tribal Bat-mask again, and beneath it, a human mask is revealed.

The story has done its work. He is asleep. His fever has broken. “He will live.”

When Bruce awakes, he finds himself in the care of a group of indigenous people from this part of Alaska. They found him dying in the snowy wilderness and took him in. Bruce wants to know how he fought off his sickness—Drugs? Antibiotics? No. He was healed by the telling of a story. The Story. Bruce can’t believe this is what he healed him. And he can’t believe that the young woman who cares for him could possibly believe this religious nonsense either. But is it nonsense?

This reminds me of Robert Joustra’s & Alissa Wilkinson’s book, How to Survive the Apocalypse: Zombies, Cylons, Faith, & Politics at the End of the World, which engages with “apocalyptic” film and television through the lens of the Catholic philosopher, Charles Taylor. Essentially, Taylor (and consequently, Joustra & Wilkinson) argue that the modern world conceives of reality and the self in radically different ways than the ancient & medieval world. We have become a society of empiricism and rationalization; of science and reason. With all the positive benefits of this shift, so too have we become susceptible to disbelief and downright antipathy for the spiritual and the supernatural. We have become “buffered” people—completely impervious to the external influence of deities, demons, and even democracies. But once, we were a “porous” people, open to spiritual influence (both good and bad) and communal thinking (again, both good and bad). Although this world definitely was particularly prone to superstitions and fancies, it was also one that was deeply aware that humanity is not a self-contained anomaly in nature. Instead, we are a race that communes with one another in the material world and God in the immaterial. But the emergence of “pop apocalypticism,” a desperate fascination with the end of the world and the revealing (or “unmasking”) of what life is really all about, has allowed us to escape the pitfall of modernity—a world incapable of believing anything it can’t measure in a beaker or observe through a telescope.

Even in this story, I see hints of the apocalyptic. Dennis O’Neil, the famed Batman writer, frames the question of what makes Batman so important through decidedly not modern eyes. Bruce Wayne’s inception of Batman, a hyper-rational crimefighter who preys on superstitions, is actually just a reception of the supernatural and an embodiment of metaphysical realities that defy rational categories—things like justice and order; charity and mercy.

Some time elapses, and Bruce returns from his journeys. 12 years of training emboldens him to try his hand at vigilantism. We see a montage of his failures that is fleshed out fully in Batman: Year One. He retreats, bloodied and hopeless, back to Wayne Manor. He collapses into a lonely wingback chair in his moon-brightened library. The shadows of the windows fall on his face, as he weakly chants his mantra, “Criminals are a cowardly and superstitious lot”—and suddenly, a revelation! A screaming bat crashes through the window; he recalls the shaman’s human mask, but now it becomes hidden beneath the bat mask. His true nature, though shrouded beneath a cowl, has been revealed.

“I shall become a bat.”

Alfred runs into the room, startled by the noise, and asks if Bruce needs a doctor.

“No. Just tell me a story.”

Post Script:

I’ll be back with Shaman: Book Two (Legends of the Dark Knight #2), hopefully, towards the beginning of next month/year. I thing that going issue-by-issue rather than arc-by-arc will help encourage me to tackle writing more often and more succinctly. Hopefully, for those of you following along, it will be more digestible, as well.

Recommended reading:

How to Survive the Apocalypse: Zombies, Cylons, Faith, & Politics at the End of the World - Robert Joustra & Alissa Wilkinson